I’m excited to share with you my speech and slides from the presentation I gave at the Narrative Summit, Game Developers Conference in San Francisco, on Monday 19th March, 2018.

EDIT: The video of my talk is also now (as of 2020) available publicly on Youtube (see embedded below), and at the GDC Vault (currently for free outside of the paywall): “The Secrets to Creating an Indie Game Franchise“.

So, for those that can’t access the recording — I’m happy to now share with you what I said, and what I showed on the day. (Hello and thank you to those that came!)

The approach I discuss here applies across artforms. But this talk was specifically for a game developer audience, addressing how the approach can be used for indie games.

Whatever artforms you work in, I’d love to know what you think!

Welcome everyone. I’m Christy Dena and I’ll be talking about “The Secrets to Creating an Indie Game Franchise”.

But why are these secrets? Why aren’t the techniques to develop a franchise common knowledge? Why aren’t we all learning how to do this as part of our craft?

You may be thinking, Christy, it’s about money. Franchises are about exploiting revenue streams. But that is the business etymology, the historical origins of the term franchise that kicked in 16th century onwards.

But for us here at the Narrative Summit, as writers, as designers, we have the problem of crafting multiple artforms into a whole experience: games, films, books, soundtracks, whatever.

Why isn’t this skill common knowledge?

It’s because there is a lot of resistance to making in multiple artforms. I know, I’ve been battling these resistances for 20 years.

You’ve heard of the 10,000 hour rule, well the idea that has stuck with people is this: if you hope to be any good at anything, you need to work at one thing for a very long time. If you don’t, you’re a “Jack of all Trades and Master of None”. So we all believe that working in multiple artforms dilutes or corrupts your creative development rather than enhancing it.

“Not Us” – It’s the belief that each artform is substantially different, and so it is not what “we” do. Writers don’t talk about media. Or game devs don’t do linear media. If it’s not interactive, it’s not us.

“Not Now” – It’s the fear that maybe your interest in more than one artform is perhaps some elaborate procrastination exercise. That you shouldn’t do it now, you should focus on one artform.

“Not You” – It’s the idea that you couldn’t possibly be a polycreative (a creative genius), someone who could create great things in more than one artform.

“Not Art” – It’s the idea that a franchise is not art.

But I’ve created, consulted, mentored and judged hundreds and hundreds of transmedia projects around the world. I’m here to tell you that a franchise is something you can learn to craft. I’ll show you how.

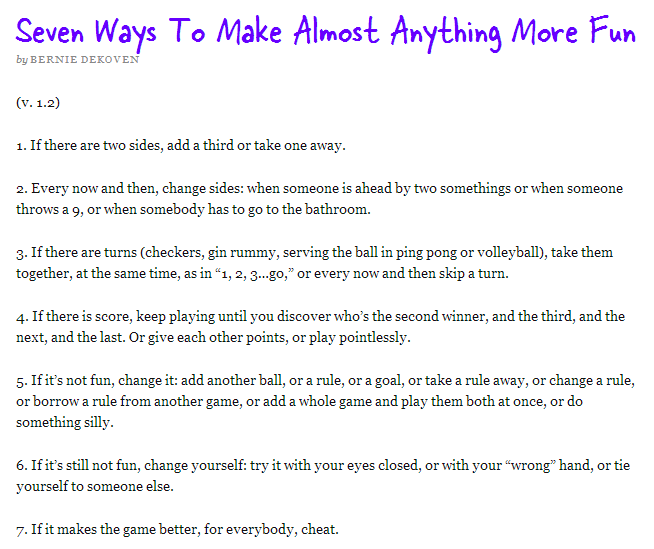

So this where you probably started?

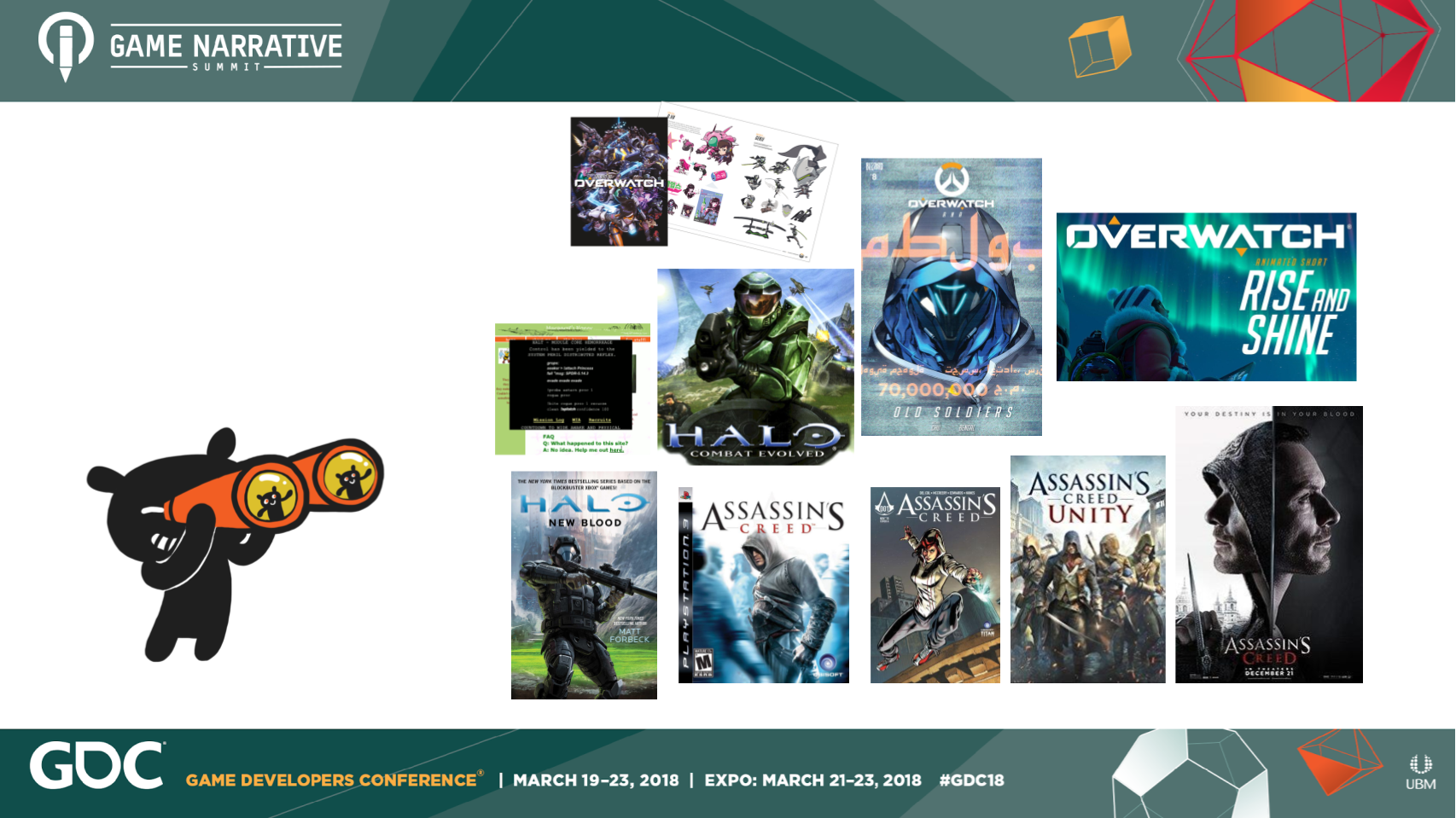

You may be looking at AAA franchises, and thinking that you need to create webisodes on youtube, and bring out novelisations and graphic novels, and a feature film, and merchandise, soundtrack, and maybe do an alternate reality game.

You can’t do those on an indie budget. You can do scaled down versions like a PDF and a webisode perhaps. But how do you decide which one to pursue?

Just knowing what artforms are available to you is not enough.

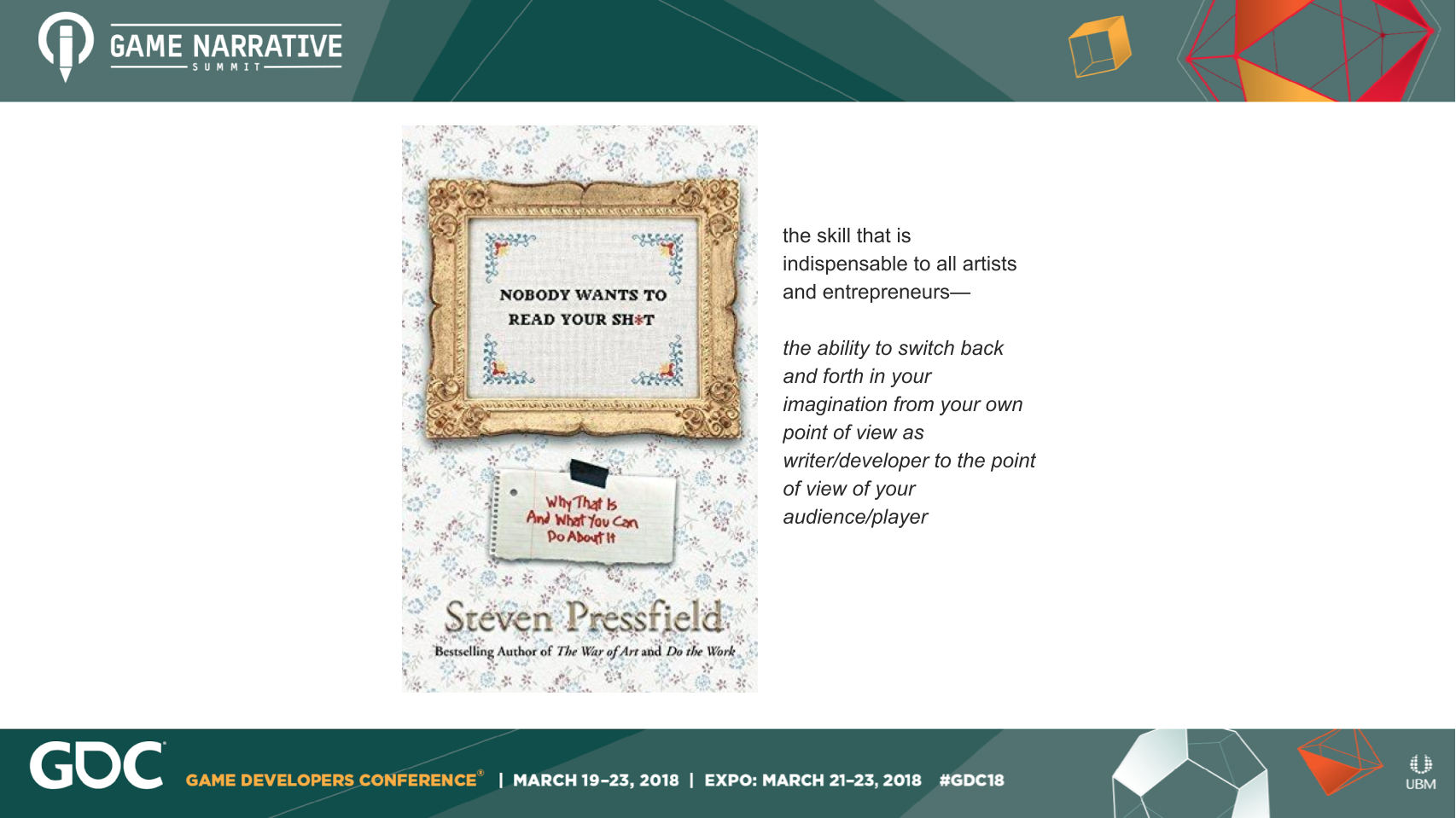

Step one. We’re starting with the premise that our franchise is shit.

Here is a book by Steven Pressfield, who wrote The Legend of Bagger Vance when he was 51. There is hope! The book is called Nobody Wants To Read Your Shit.

He learnt this when he was working in advertising, where nobody wants to spend time with your advertisement.

He explains that once you start with the idea that nobody automatically wants to read your shit, you develop empathy. You ask yourself Why don’t they want to read it? Why don’t they want to play my game?

And with this you “acquire the skill that is indispensable to all artists and entrepreneurs—the ability to switch back and forth in your imagination from your own point of view as writer/developer to the point of view of your player.”

You’re thinking about what the player is thinking and experiencing at each point.

This approach is behind successful projects in all artforms. So let’s look at how you can action this and how this relates to franchises.

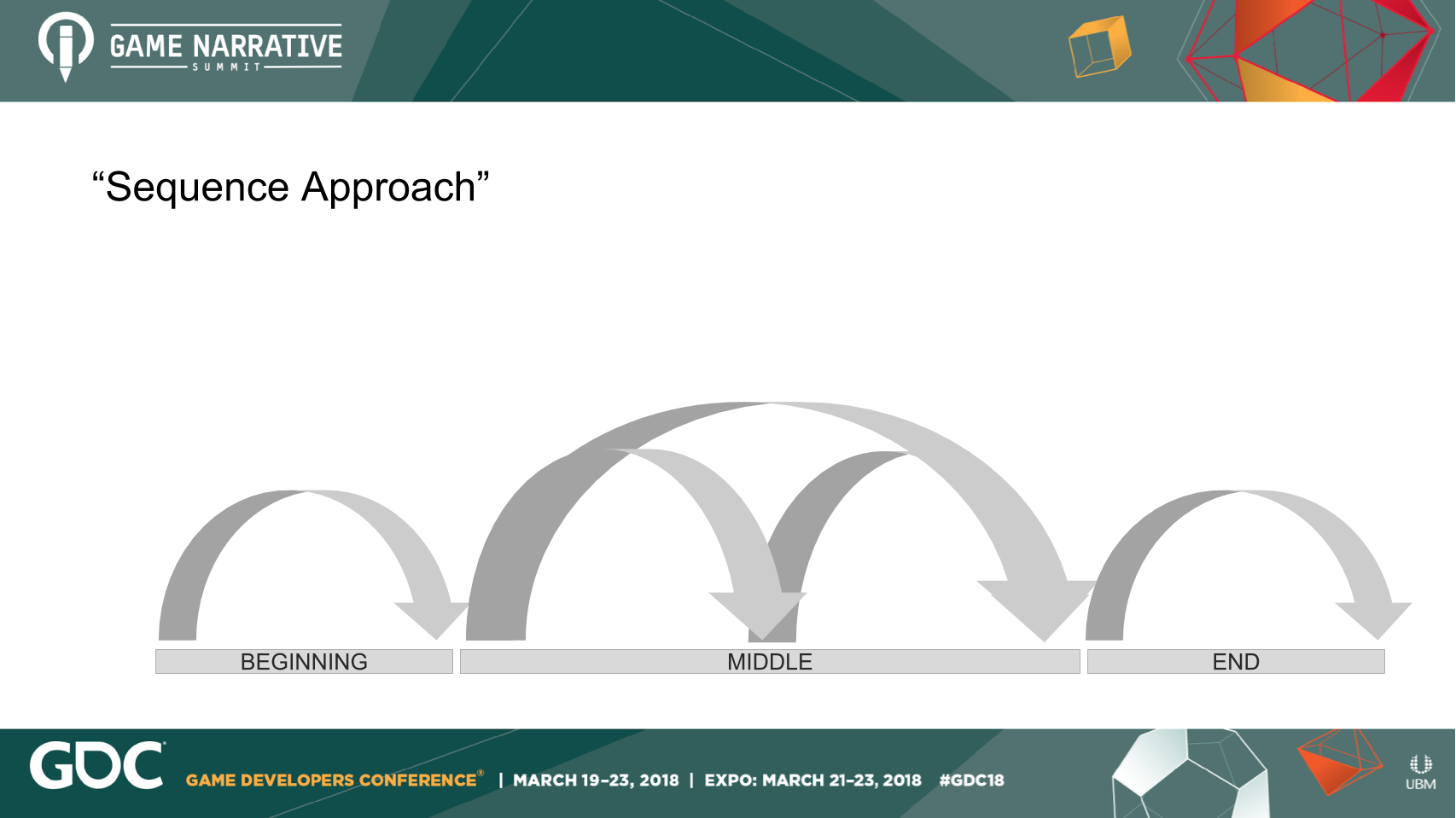

In Hollywood, there is a screenwriting technique called the “sequence approach” – some of you will be familiar with it.

It was developed by Frank Daniel who, after analysing hundreds of successful screenplays, realised there was an emerging best practice that would help us all make great screenplays. Frank was a screenwriter himself, playwright, and novelist, who had a masters degree in Music and a doctorate in film. He influenced generations of filmmakers in his roles which included being the first Artistic Director of Robert Redford’s Sundance Institute.

Interestingly for us, his sequence approach “focuses on how the audience will experience the story and what the writer can do to make that experience better.”

So what is the sequence approach?

Basically what it does is take the existing structure we all use and we see here of a beginning, middle, and end, and adds shorter sequences.

But the emphasis here is not the shorter sequences, but that these sequences are driven by an audience question.

The crucial part of this approach is to think about what drives the audience interest at each point of your film. What questions drive them? What are they thinking about.

You’re the one that designs that interest with a ticking clock, dramatic irony (when we know more than the characters for instance), and importantly dramatic tension, when we withholding an anticipated resolution.

This thinking about the audience experience, what is on their mind, what they know right now, what they’re expecting next, is common to all successful works.

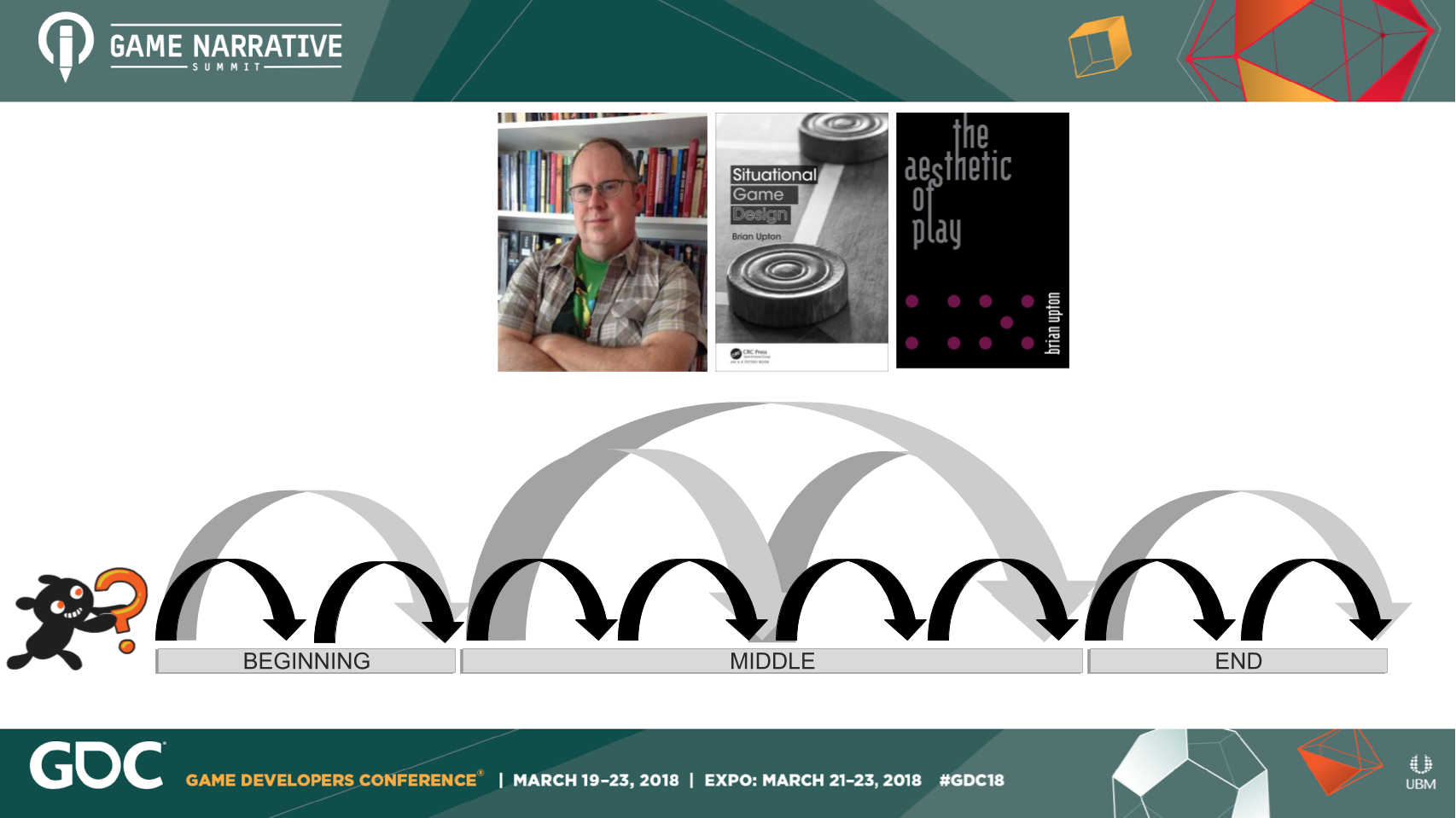

For example, Brian Upton, who was the co-founder of Red Storm Entertainment where he designed the original Rainbow Six and Ghost Recon; and was Senior Game Designer at Sony. He talks about “situational design” where “nexus of play is not in the transactions, is not in the actions, or the interface, the nexus of play is inside the player’s mind.”

He talks about the importance of designing for player anticipation.

OK, so how does this actually work in a game? And a franchise? Let’s have a look at What Remains of Edith Finch.

Our first question is one that seems will drive us to the end of the game:

“What remains of Edith Finch”? “What does that mean?”

As we play we find one that comes very early is “How do I get to the house?”

The designers strategically placed the house in the distance, (a “weenie”), to get us to think about where we are to go, what we are to do.

And then they mention we have a key. So the developers have us thinking “What does this key open?” “I need to find something that needs this key.”

You see how these questions work as objectives?

So if we’ve had those previous small questions answered to our satisfaction, then it is more likely we’ll continue to the rest of the game.

In fact, Brandon Sanderson, best-selling science fiction and fantasy writer, talks about this technique as a “promise”. He doesn’t see it as a question, but as an open bracket and closed bracket. You promise that something will happen, and then follow it through. You indicate to the reader that your story will be about something and deliver on it.

Now all of you know this in terms of genre – you know that when you promise a player that this is a party game, it is a FPS, it is an openworld game, a horror, an action adventure, a comedy, you have to meet the expectations of how those genres operate. It’s a feedback loop where our players engage in a continuous reappraisal, and these promises are one factor in how they decide, and why we must deliver.

I really like the notion of a “promise” because it about what players thinking about, it is also what we’re signalling to them we will provide, and then too, with “promise”, it implies we have a responsibility to honour it.

So how can we use this for our shit franchise?

If we agree we have this best practice of switching between our POV and our players, of designing for leading promises and keeping them, then we have an approach that we can use across artforms in our franchise…

You see, we can think about the questions in our players’ minds BEFORE they get to our game.

WHY do our players want to play our game?

Then WHY they want to watch our webisode? Why they want to read our graphic novel? Why they want to listen to our soundtrack? In the words of my colleague Marc Ruppel, it is what happens between media that is the most important.

And we’re not alone. A study by Kultima and Stenros (2010) looked at game experience models and posited that “If we think about the perspective of the player, there need not be any separation of the different parts of the experience.” The experience for players starts before they’ve even opened the game.

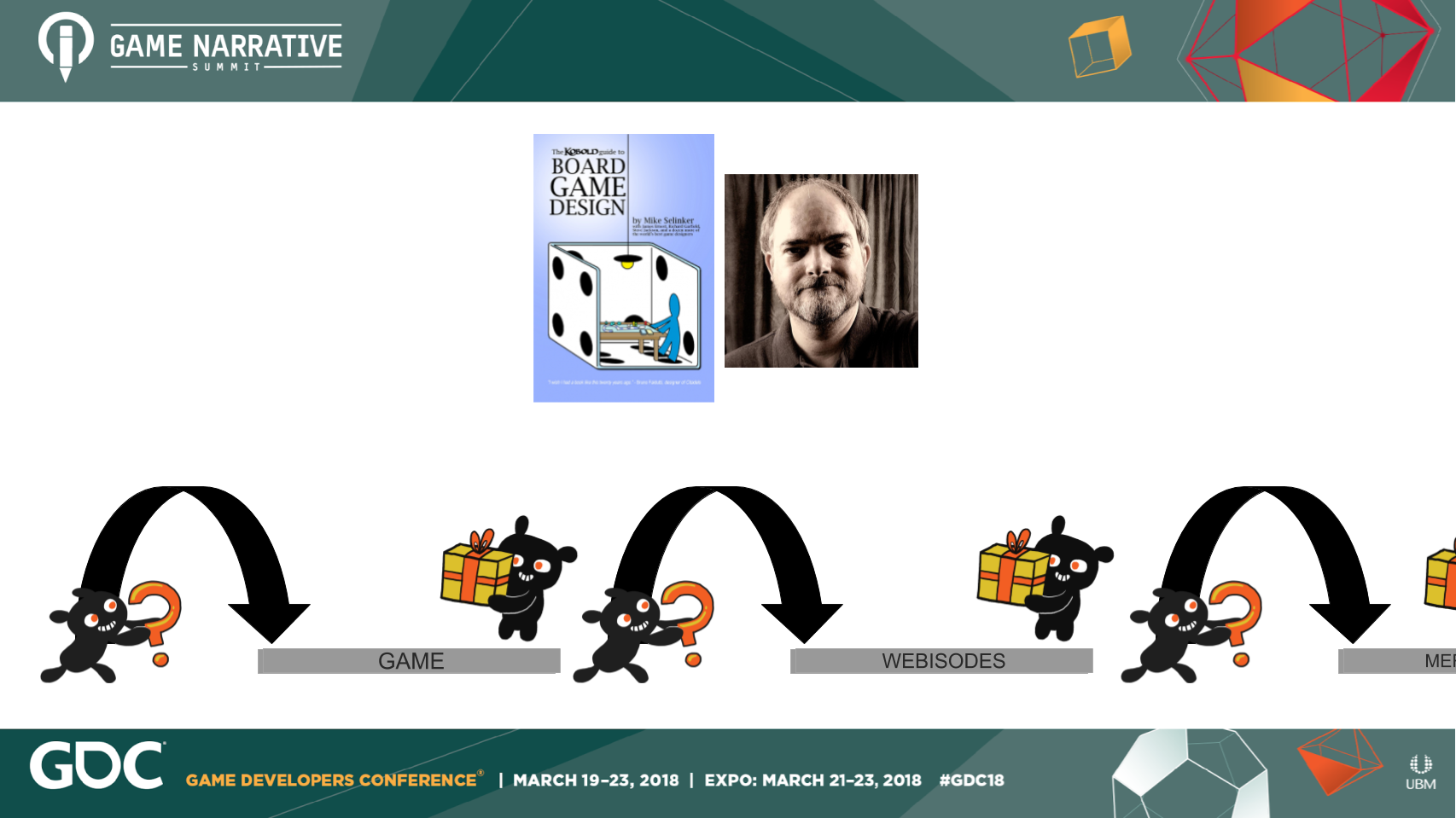

James Ernest, founder of Cheapass Games, former writer at Wizards of the Coast and former Game Design manager at Microsoft.

He says, “If I had to pick one thing that games should have […] it is “a reason to play”. I don’t like to say “a hook” because that implies superficiality. It’s not just a foot in the door, it’s the reason you keep coming back. It’s what distinguishes a hit from a flop, between two games that are empirically identical.”

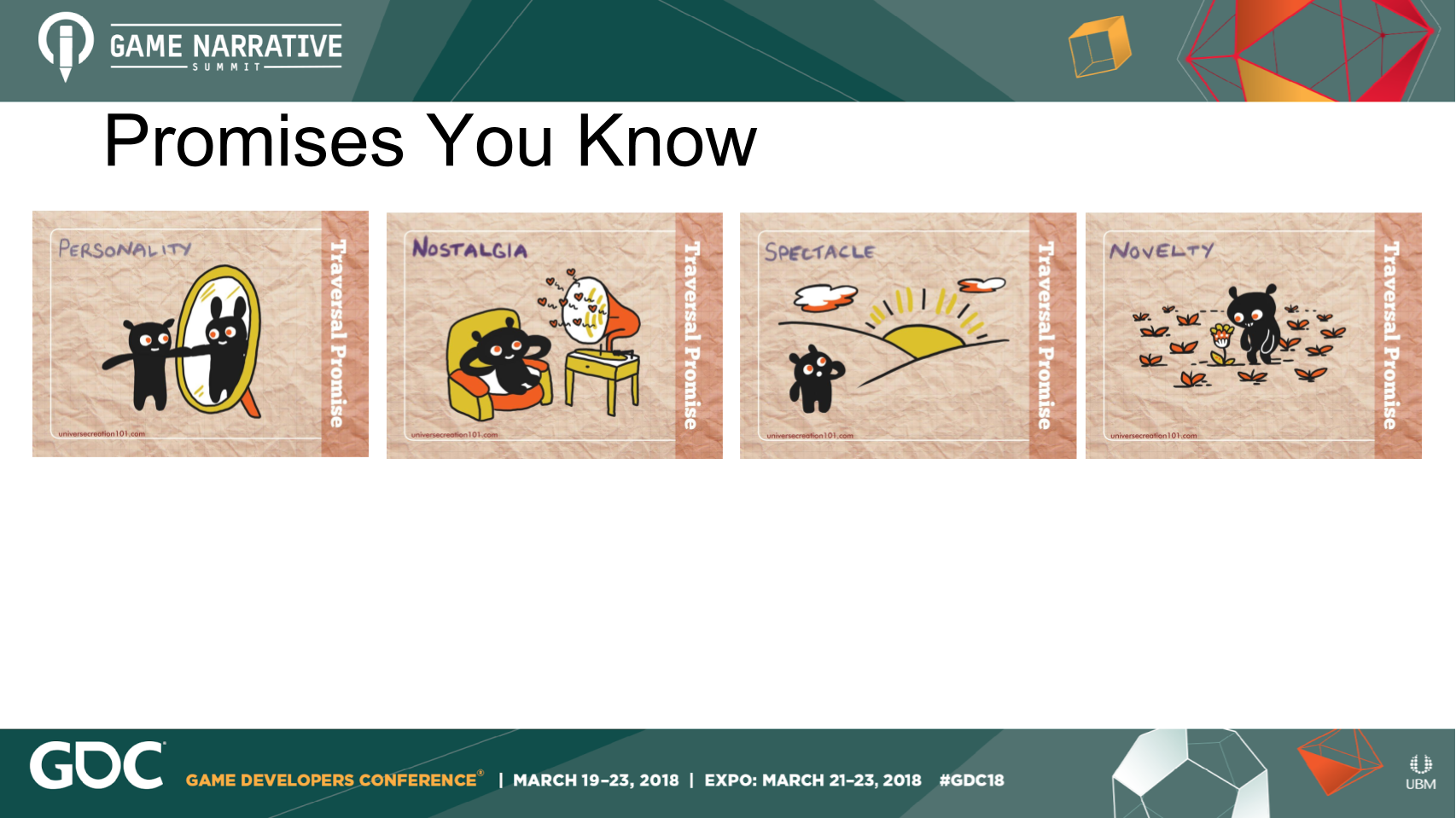

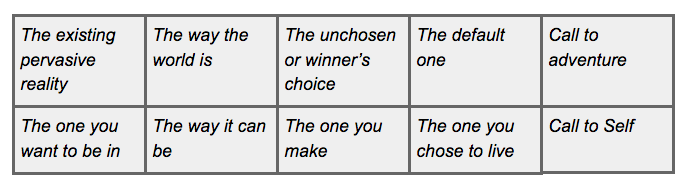

OK. So what are these promises? These promises for franchises?

What are the promises that invite our players to play the game, then watch a film, to listen to music, to read the book?

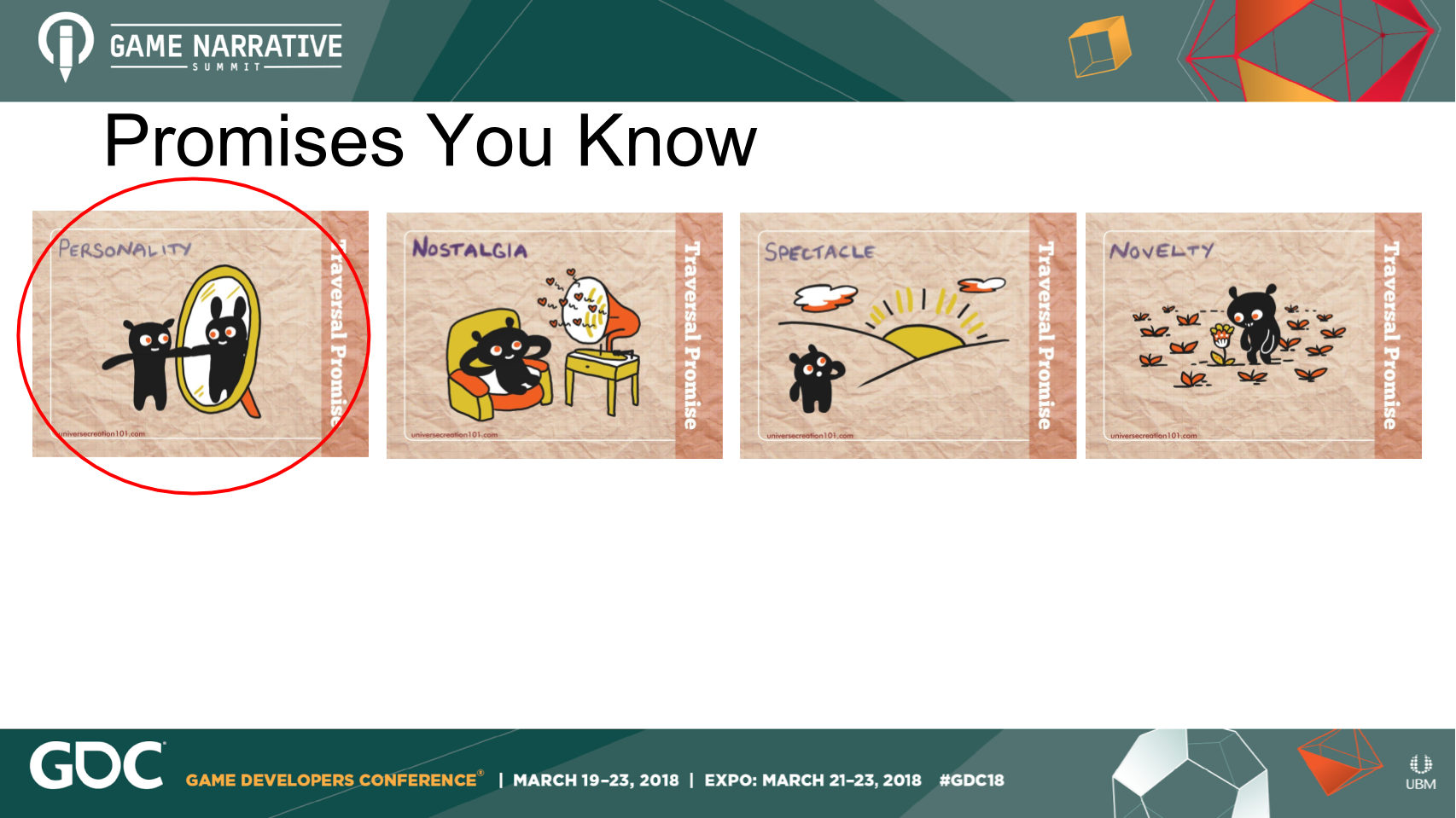

You already know a few.

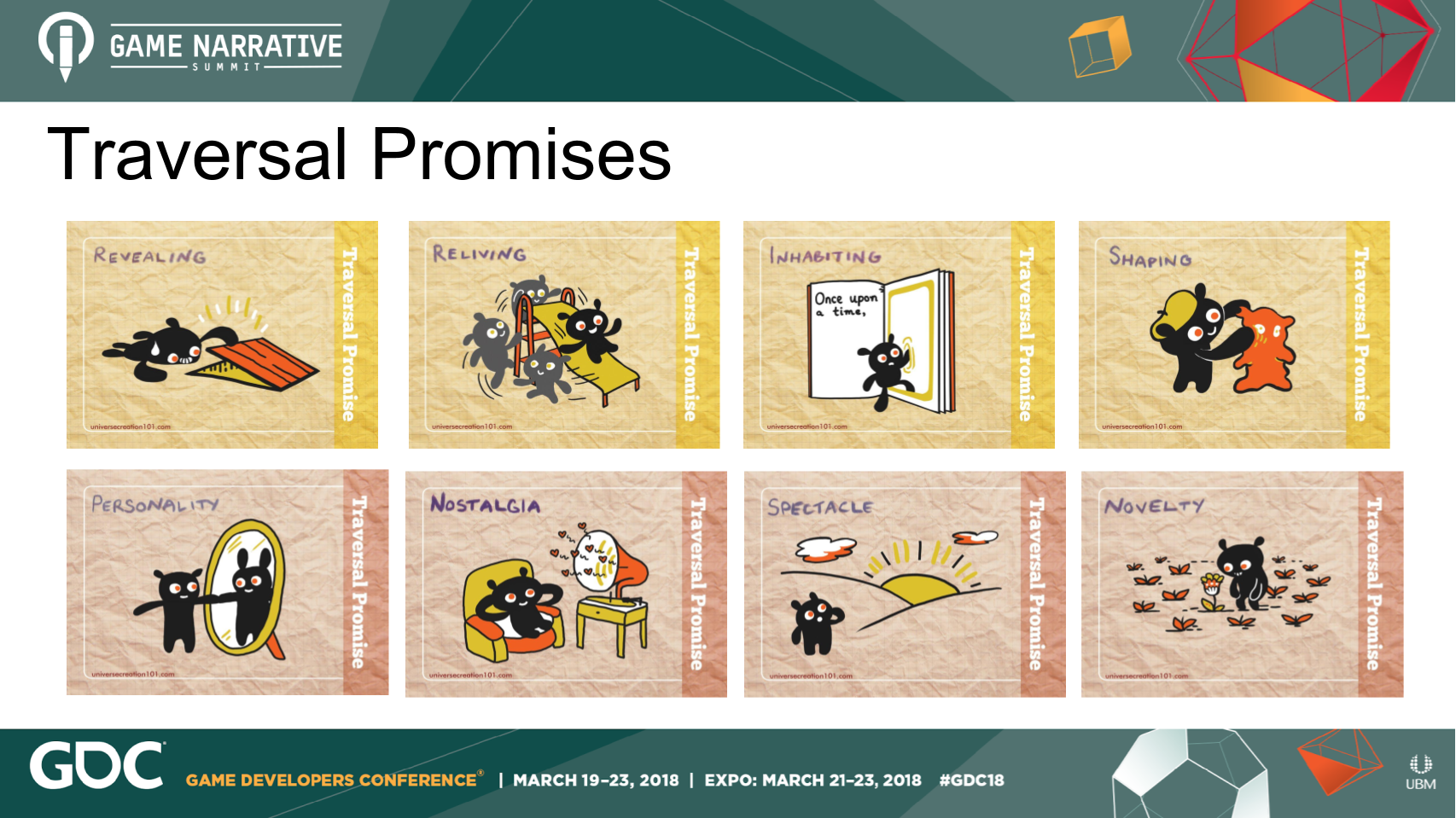

You experience them all the time. We have Personality, Nostalgia, Spectacle, and Novelty, to name just some.

[I just want to give a quick shout-out here about these cards, and all the illustrations you’ve seen in this talk. These are custom made by my wonderful illustrator Marigold Bartlett for my forthcoming book & design kit.]

You know the lure of “personalities” or “stars” can have on a project. It’s Angelina Jolie playing Lara Croft, or Stephen Merchant voicing Wheatley, the characters themselves, Lara Croft, or auteur directors.

It’s filmmaker Eli Roth being brought in to do the animated trailer for Dark Souls 3. It’s musician and filmmaker Rob Zombie being brought in to do an animated short for Assassin’s Creed Unity.

It’s the appeal of Rami for Vlambeer games.

So what is the personality promise? The personality promise can be credibility, but it can also be the promise of being with someone who lives a life we want to live, to be.

Nostalgia will be familiar to you.

It in the 8-bit games, pixel games, such as Sword and Sworcery and Nidhogg, and 1930s-style animated game Cuphead.

What is the nostalgia promise? It’s the promise of positive memories, the comfort you feel with those memories. The thing about nostalgia, if you don’t have positive memories with them they won’t be a promise you’re after.

Spectacle is a promise we know too.

Think of a Transformers movie trailer and you get what spectacle can be about.

It can be many things that widen our eyes in some way, it can be a visual beauty, such as the blue and green marine life of Abzû, or the black splatter on white in The Unfinished Swan, or the photorealism of Assassin’s Creed.

What is the promise of spectacle? It’s the promise you will experience of awe.

Related to this is Novelty, and how things that aren’t the status quo draw our attention. It is Pokemon Go!, which for many introduced them augmented reality gaming. It is Johann Sebastian Joust, where you’re not using screens but glowing move controllers and dancing around each other. It is Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes, where instead of playing a game by yourself in a VR headset, you call out bomb diffusing commands to a mate on a headset. The promise is stimulation through change.

But there is also a social promise operating in these projects. Indeed, it may be the more of these promises you offer AND deliver on, the higher likelihood of not just player acquisition (gaining new players) but also player retention (keeping your players).

So what are other promises your players want and you can provide in a multi-artform context? Why, on top of all these other promises, would players STAY with your game franchise when you change artforms? Why not just to a new property? To new IP?

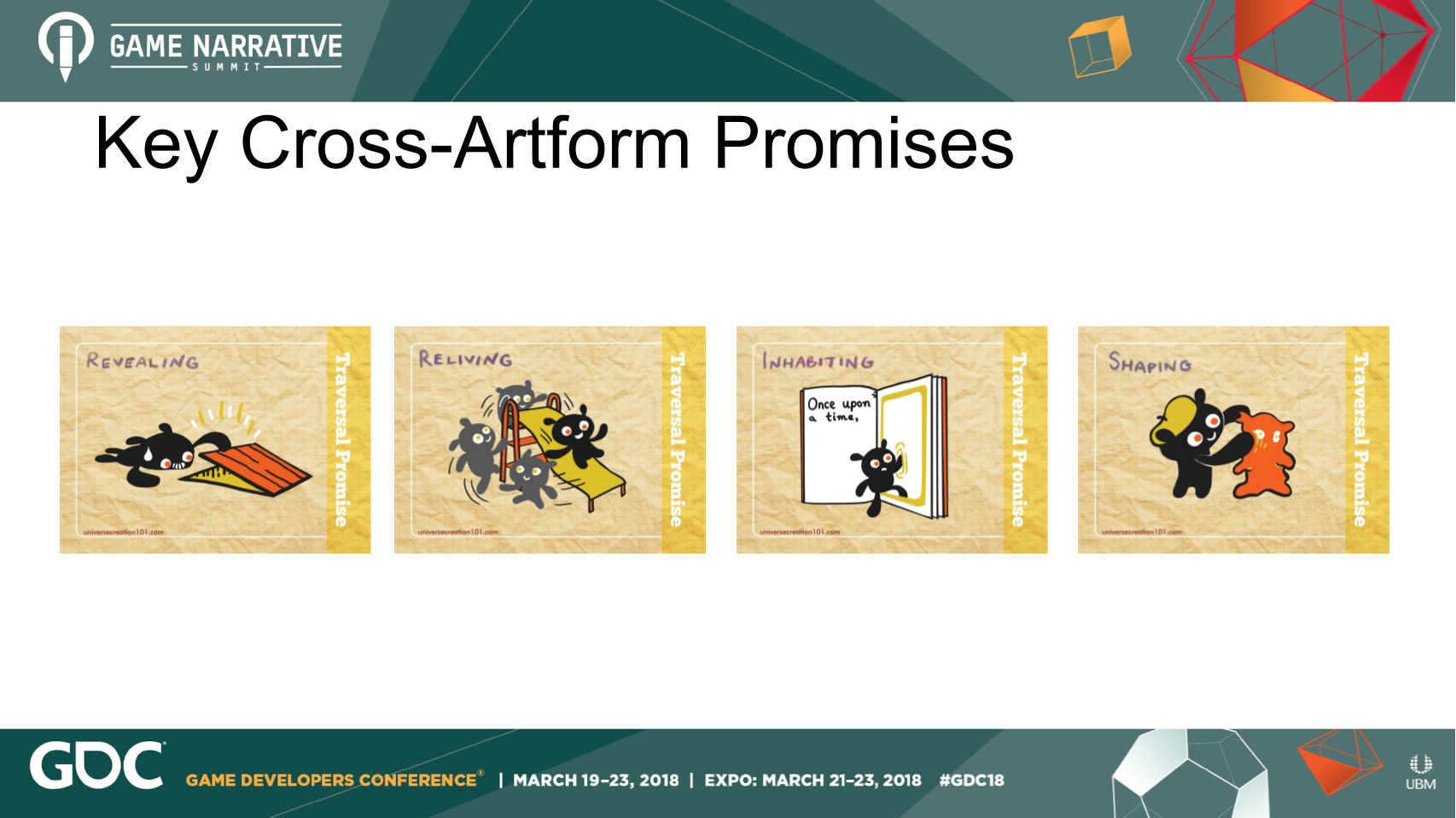

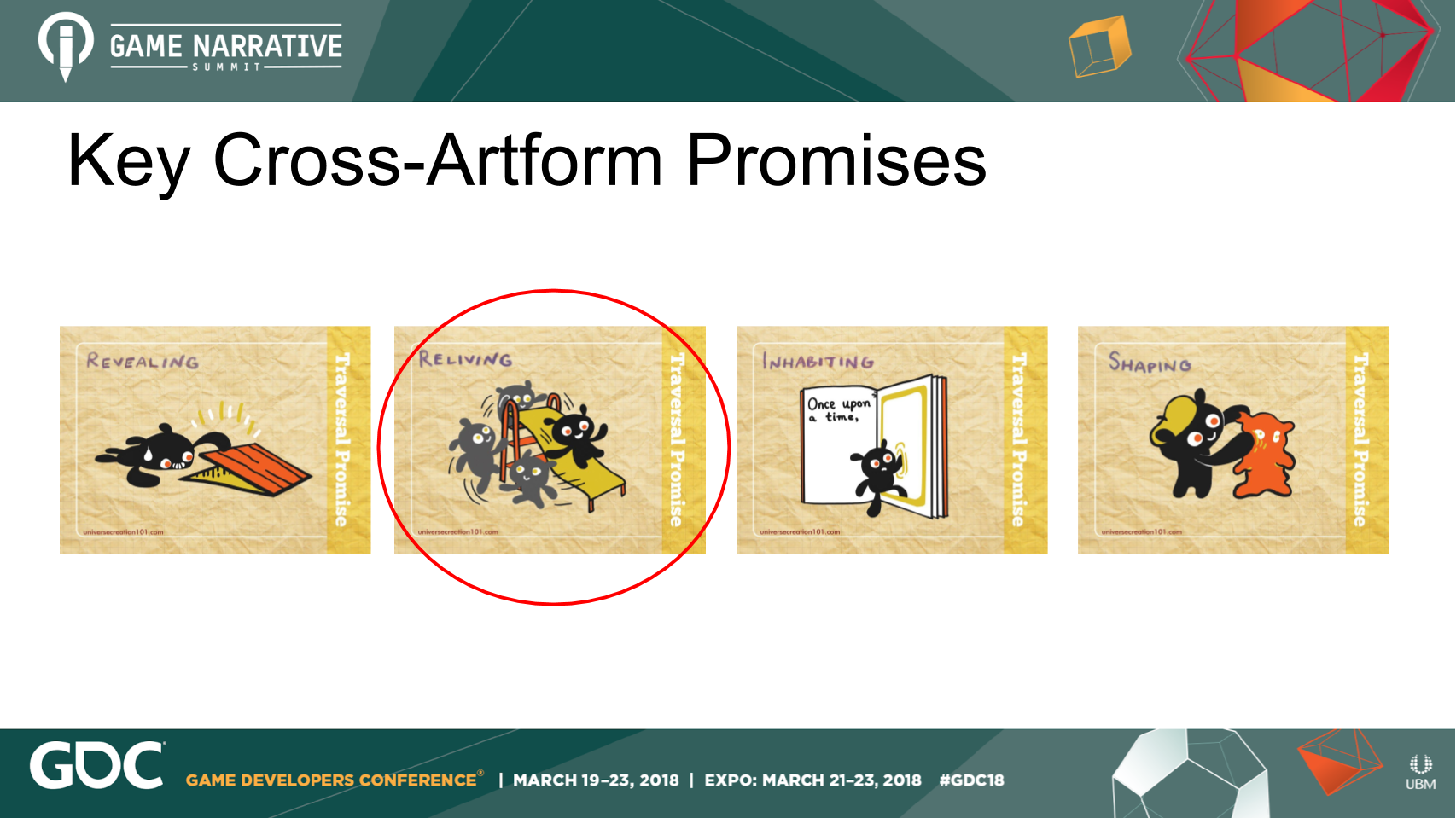

These are key cross-artform promises. The promises that help your players cross artforms.

They are, if you like, the genres of crossing artforms.

They are why your players go from your game to your soundtrack, to your graphic novel.

They are the promises you signal and then keep.

The Revealing Promise is about revealing more. More information, more characters, new mechanics, new stories.

It is a sequel, a prequel, anything that primarily offers a new insight.

It’s when you get the end of a Kentucky Route Zero episode and want the story to continue, you want to find out what happens next. Let’s look at some examples.

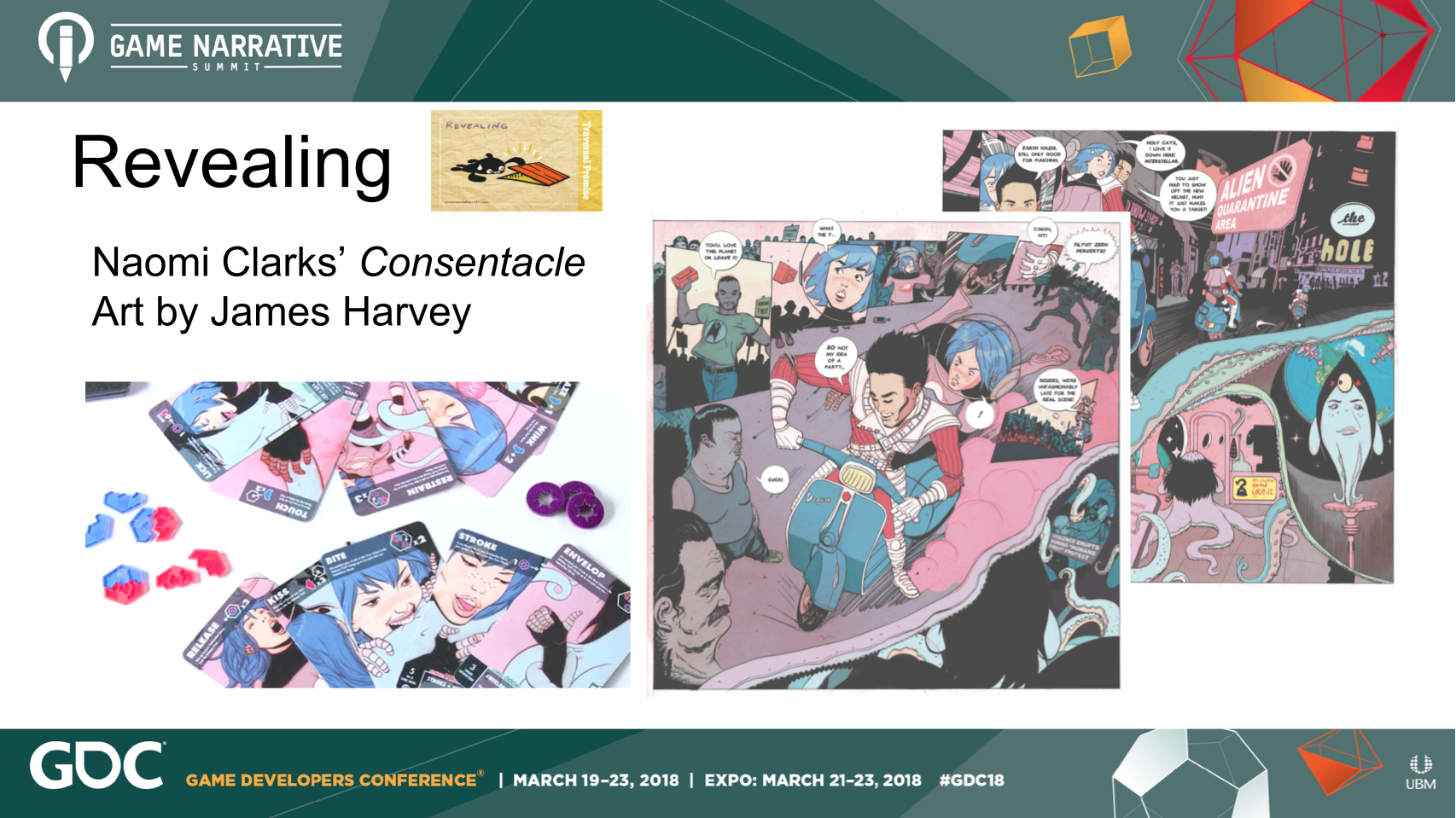

The Revealing Promise is in the card game Consentacle, where you’re engaging in a mutually satisfying and consensual intimate encounter with an alien.

You can go straight into playing the game, but Kickstarter backers also have the option of a 12 page prequel, where they find out how Kit and Dup meet and what stands in their way. [Edit: The prequel comic is now 10 pages.]

It is something that can be enjoyed before playing or after, setting up the character motivations or giving context.

And then there is the game That Dragon, Cancer, that tells the true personal story of Ryan Green and his family as they raise their son Joel who is diagnosed with terminal cancer.

We follow the family through the hospital treatments, the playgrounds, the church and then Joel’s afterlife when he dies at age 5.

In what is perhaps the most heart-wrenching prequel there is, the book released almost a year to the day before his passing is titled He’s Not Dead Yet.

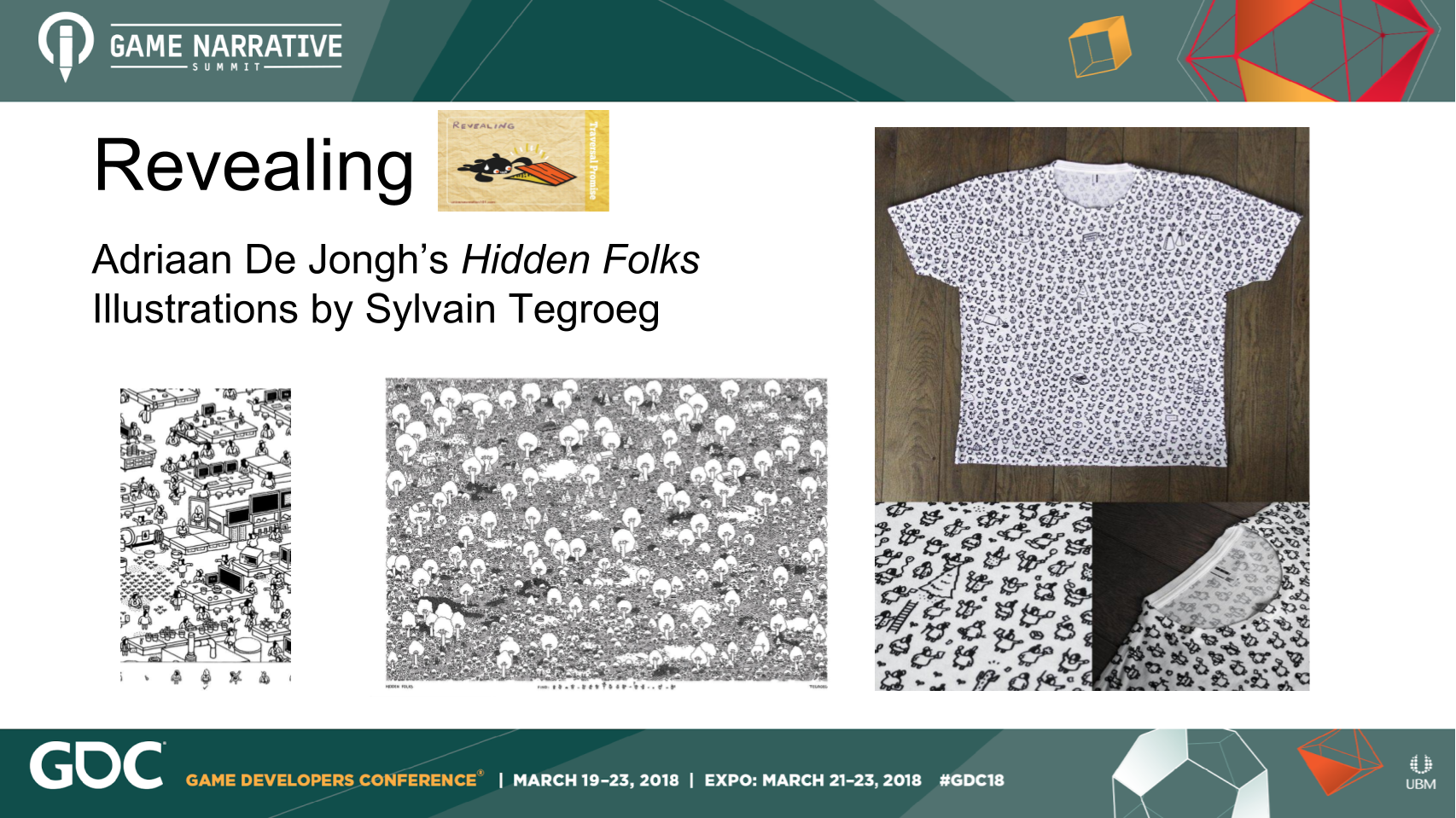

And how about the hidden object game Hidden Folks, where you can also keep playing more games with the playable t-shirt and playable poster.

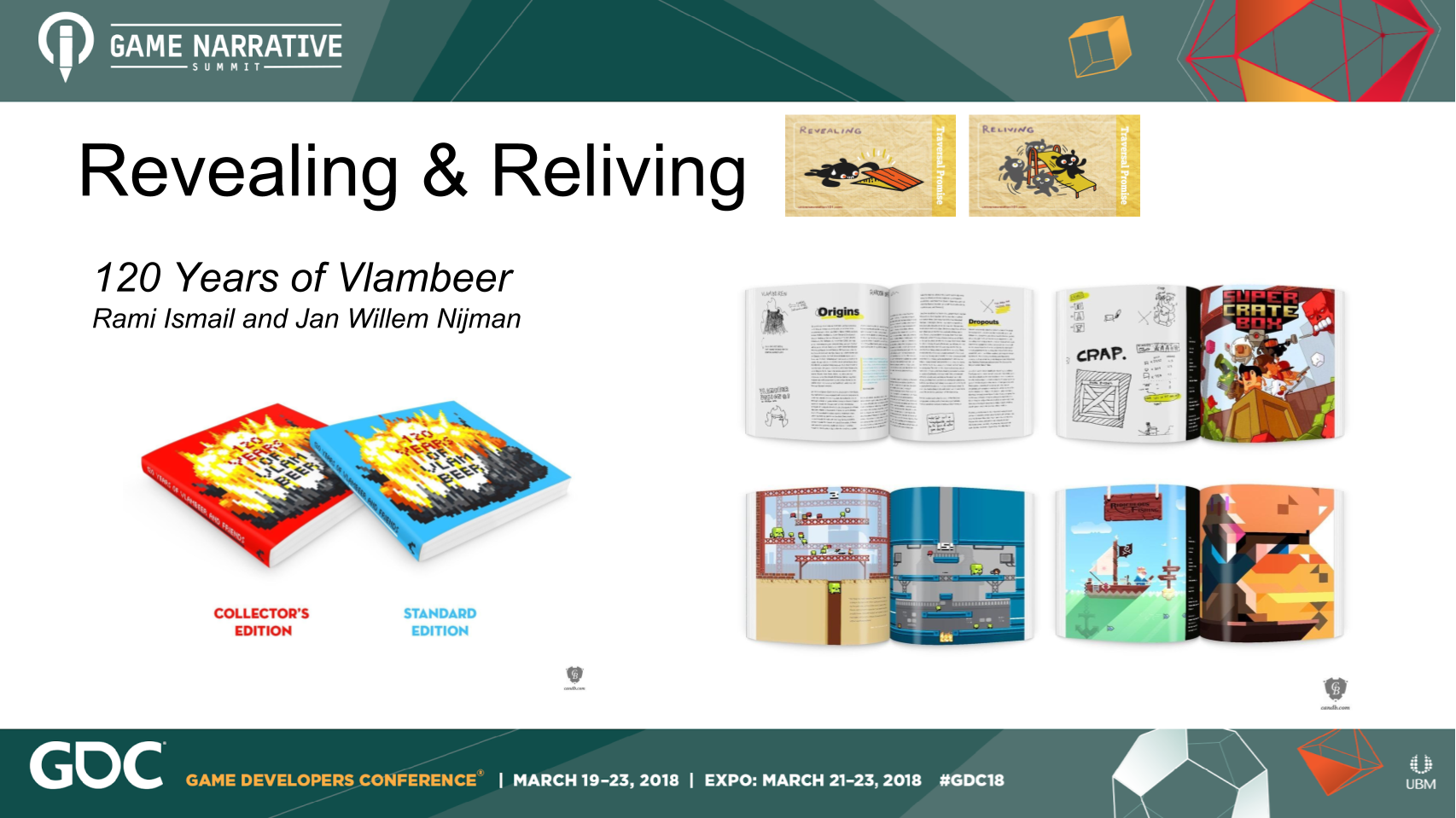

The revealing promise is also about meeting the interest in revealing more about the creation of the game, or games in the case of 120 Years of Vlambeer. Their collection includes art, but also their game and audio design, and studio beginnings.

Now you may notice I have the reliving promise card there too. Because in some way players are reliving moments from the games.

But if we look at fan interest in Art Books, we see a definite leaning towards the revealing promise more than the reliving one.

Many say they prefer to see more work-in-progress than final art. This is an example of how knowing these promises can help with your decisions.

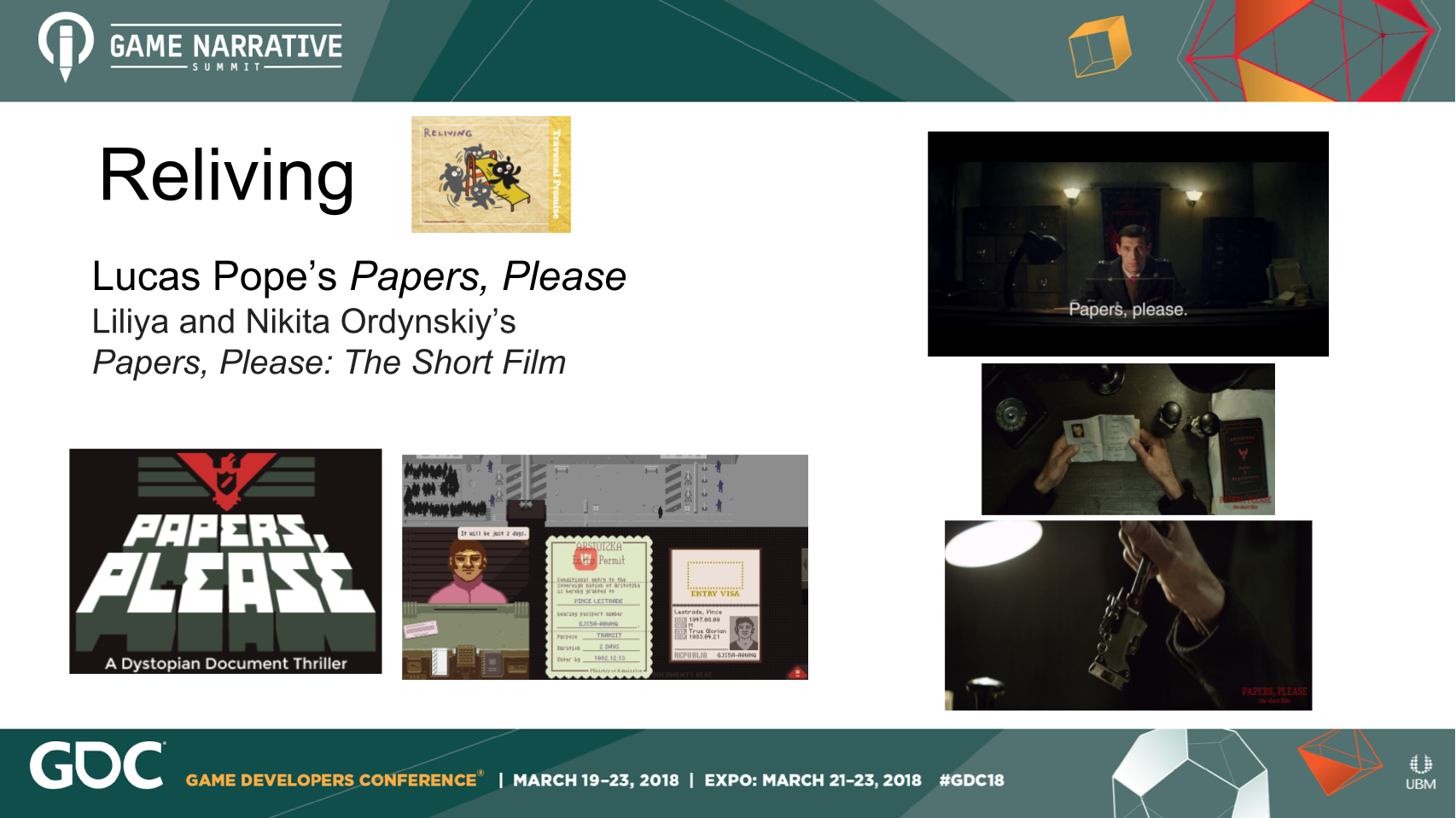

So let’s look at the Reliving Promise. It is about providing a “dependable pleasure”. What that pleasure is, is determined by both you and the players.

It is the eternal question of what stays the same and what changes?

Often audio moments continue across projects. It’s the submarine clang that Grant Kirkhope took from the Goldeneye film and put into the game. Or the music and opening sequence flying over the pine-trees and mountains for Twin Peaks. Changes can happen around those dependable pleasures.

The Papers, Please short film gives us key moments that we know from the game.

In the live action film, we watch as the inspector (who we played in the game), has to decide who to award entry.

It includes the mechanics of moral dilemmas, the focus on the passport, the clink of the stamp, the high stakes of moral outcomes, and the nation’s motto in the end.

But is it too much the same though? It promises the familiar, but is it too familiar?

For Brain & Brain’s Burly Men at Sea, they promised a great reliving experience. After playing through their folktale adventure, which you can play through again to explore different regions. Each playthrough is assigned a code and is depicted as a book in a digital bookshelf. What you can also do is go to their website and enter the code and be sent a printed book of your personal playthrough.

But, the art, while the same, was different enough in places that I didn’t feel as if I was experiencing key moments again. This is an example of what Donald Norman calls “the gulf of execution” – when the actions that we provide do not correspond to the intentions of our users. Not meeting the promise.

But if we as creators know what our players are expecting, we can nuance the emphasis between the familiar and unfamiliar accordingly.

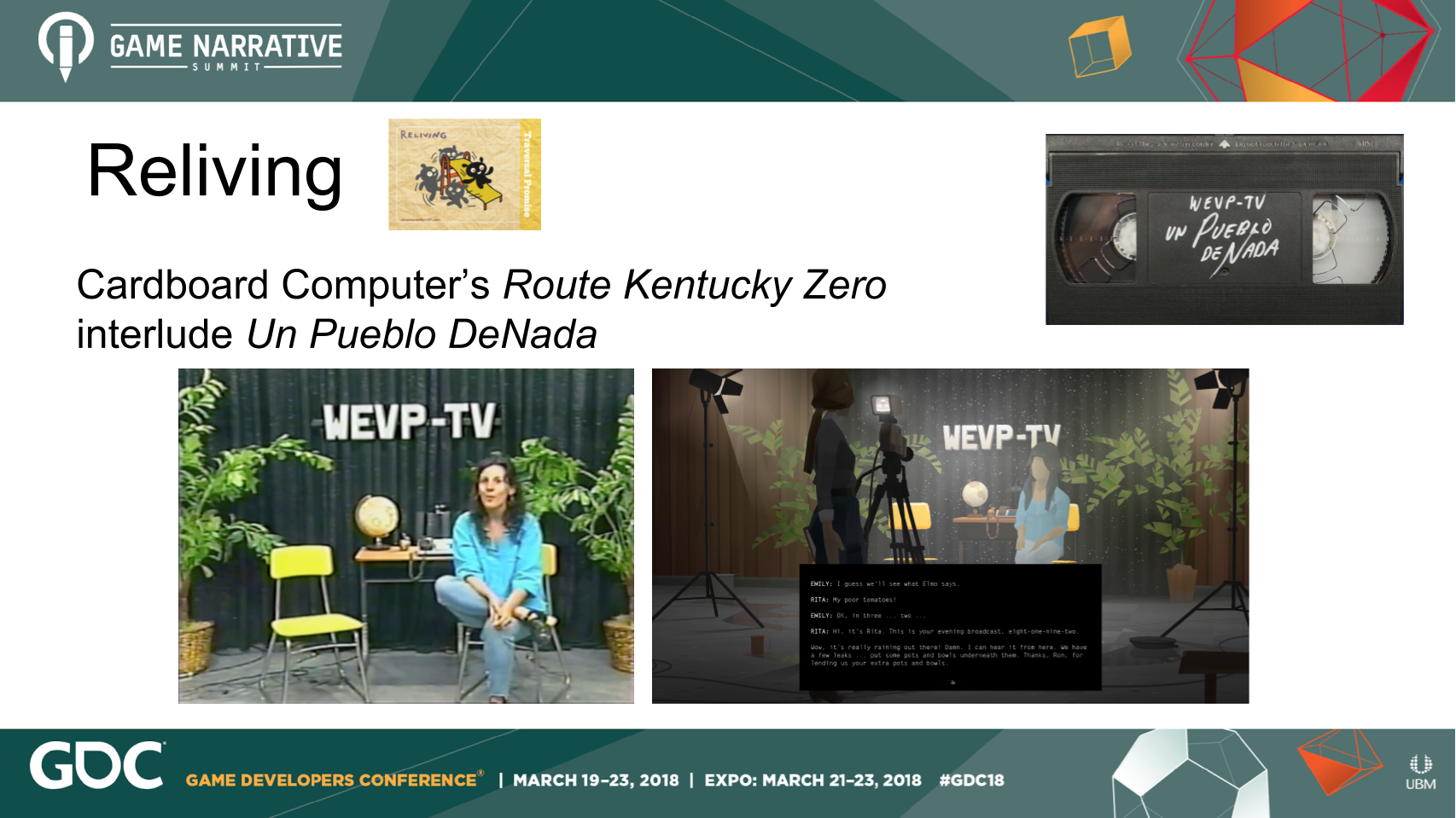

Kentucky Route Zero has “interludes” which are games and stories and plays that happen between each digital game Acts.

The most recent features liveaction video footage of the local community television station and a digital game of the video. Having the same event juxtaposed in these two artforms, you can’t help but look for the differences and revel in them. The creators are very aware of the players experience of these projects and rewards them with lots of intertextual references between these two works.

In the live action video, Rita for instance mentions we probably already met the guest Maya, an allusion to us having met her in the game. These references go further, to not just all the games, but also as Robert Yang spoke about on his blog, to meta player discussions.

One thing that Cardboard Computer also do is use a lot of the “inhabiting promise”.

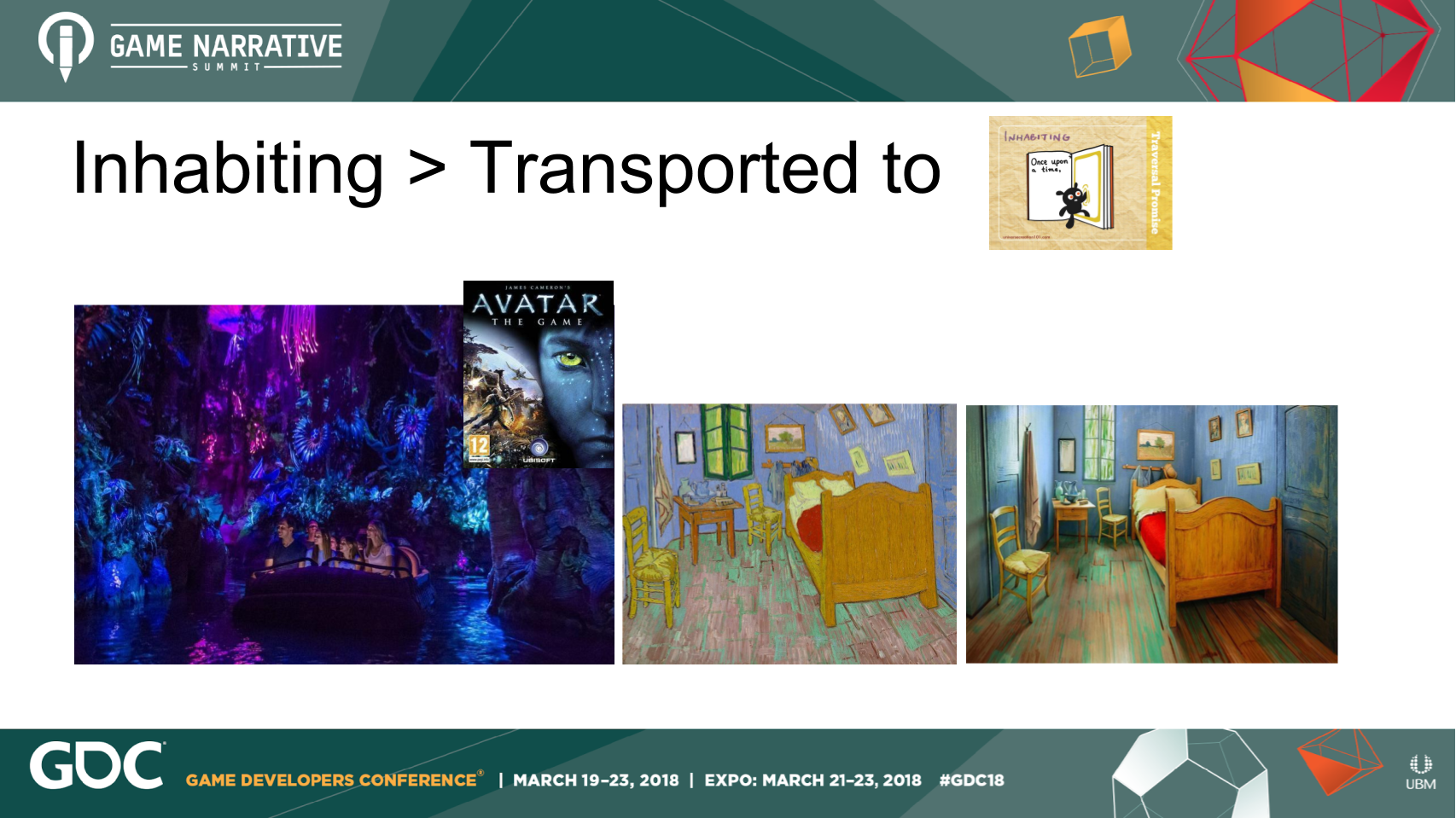

There are two key ways the inhabiting promise can be met, the promise to be inside the created world.

Inhabiting can occur via transportation to a created world. Or it can happen when the created world transports to our world.

It is being able to explore the alien world of Pandora at a theme park.

Or being able to enter the painting of Vincent van Gogh’s “The bedroom”, as the Art Institute of Chicago offered when they teamed with AirBnB.

So you transport away from your world, and immerse yourself in the created world.

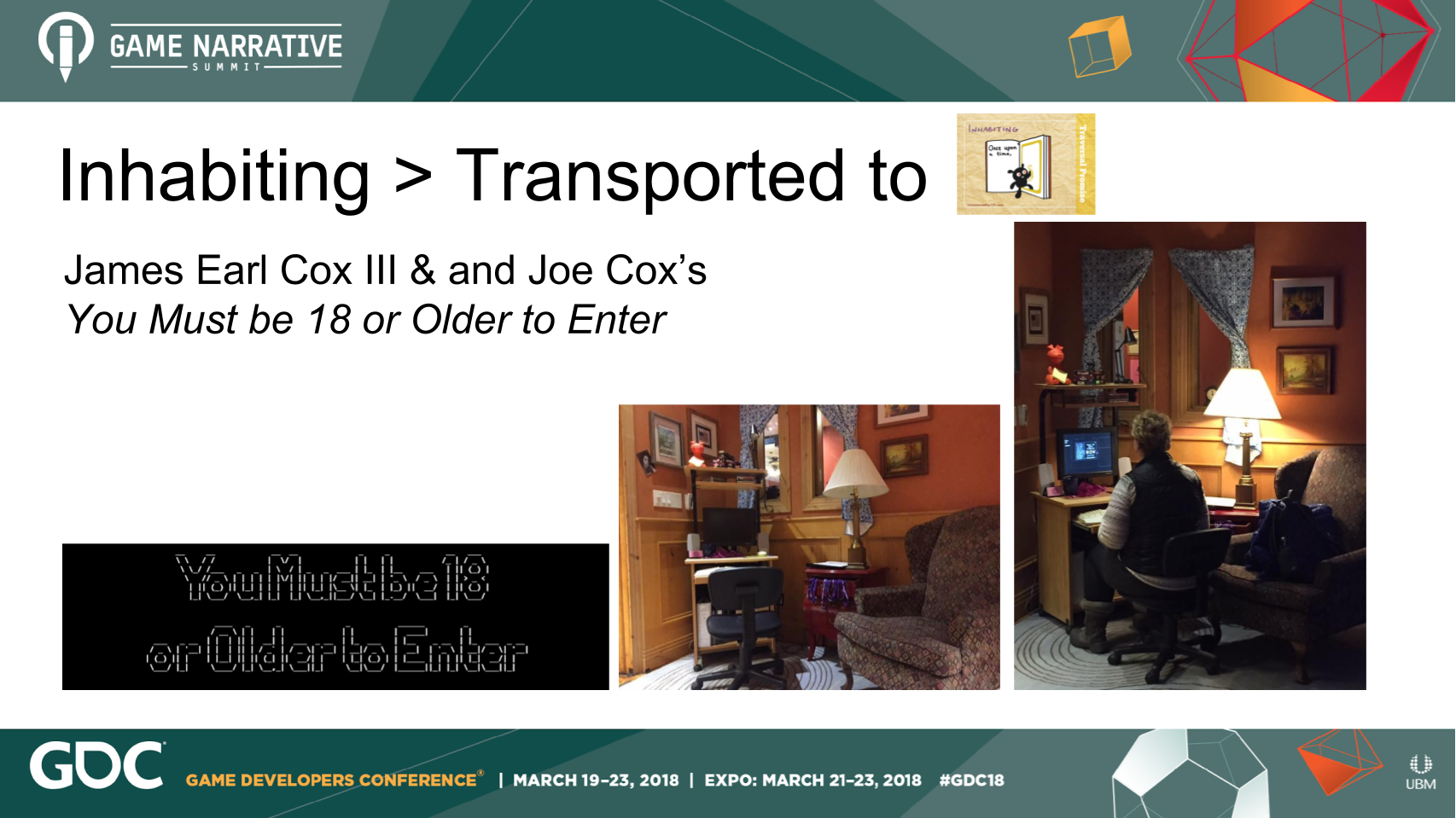

It is the installation for You Must be 18 or Older to Enter, where the conceit is: “You’re alone at home, and you heard about this thing called porn at school.”

This installation at SlamDance has you set-up in a room. The nifty thing about this experience is that on the other side of the “window”, there were people getting their photo taken. So when the game suddenly takes over with loud porn groans you literally experience the momentary panic or embarrassment at being caught looking at porn. So the key mechanic of game is there in an embodied experience.

The reverse transportation is when the created world enters your world, the player’s world.

An example is Question’s The Magic Circle, which is meta-fictional game where you play the protagonist in an unfinished game. You can wander through the unfinished world, and hear the trials of the designers stuck in development hell. Now the company Question have the usual website and press-kit, but they’ve also created the website for the fictional developers, their social media and their own press releases. The world overlaps our own.

There is Jacob’s Paradigm game, a surreal adventure game set in a strange and post apocalyptic Eastern European country. Jacob has the protagonist existing on Tinder, there is a travel guide for the fictional country and book on the fictional religion, and you can get the floppy disk for the game (one of 356 floppys) which of course doesn’t work. But we have the nostalgia promise operating here. Now I have bought the floppy disk, but not the game yet. So this is an example of different artforms appealing to different people, but also potentially being a conversion tool.

There are so many examples of the inhabiting promise, the Alan Wake Files book you can buy that is credited to the in-game author, the play in Kentucky Route Zero you can buy that is credited to the in-game character, the PipBoy that you could buy too.

In fact, this inhabiting promise is such an allure that in the upcoming Star Wars theme park there are areas where you will only get in-fiction merchandise.

The Walt Disney Imagineering Executive Creative Producer Chris Beatty explained that “in order to create truly authentic experience that felt like you were on a planet from the Star Wars universe, they’d only sell certain merchandise, and that merchandise was based on the idea they are made by characters […].”

Here we have both of the inhabiting promises: created worlds we can go to, and then can take home to our world.

The Shaping Promise is something different. We all know fan fiction, and the creations fans make in response to your creative projects. You have no control over that. Players do that if they want.

But when you as developers facilitate it happening with creative projects, you’re working with the Shaping Promise.

It is the promise of being able to make the project more like us.

An example is mods.

And recently we have one with the Game Master’s Toolkit Defiant Development have offered for players to make their own encounters and full challenges. Which they said they knew their community would want.

It is also the experience of figurines – which can be a way for us play out our own adventures with the characters we love and want more of. Like Boba Fett and even Maisy.

Indeed, you could conceivably say that the more of these promises your offer and deliver on, the more you are likely to appeal to a range of players and keep them.

I have mentioned some key ones today, not all.

So when you’re deciding what media you’ll choose, it isn’t about what the big studios do, or even what artform is popular necessarily. Everyone may be doing graphic novels, but it may not be of interest to you personally, or fit your gameworld.

The key we’ve learnt here today is to not decide purely based on the object, the media. The critical aspect that will make or break the design of your indie game franchise is to think about what your players are looking for. They’re looking beyond your media to something else. To the revealing, reliving, inhabiting or shaping promises you signal.

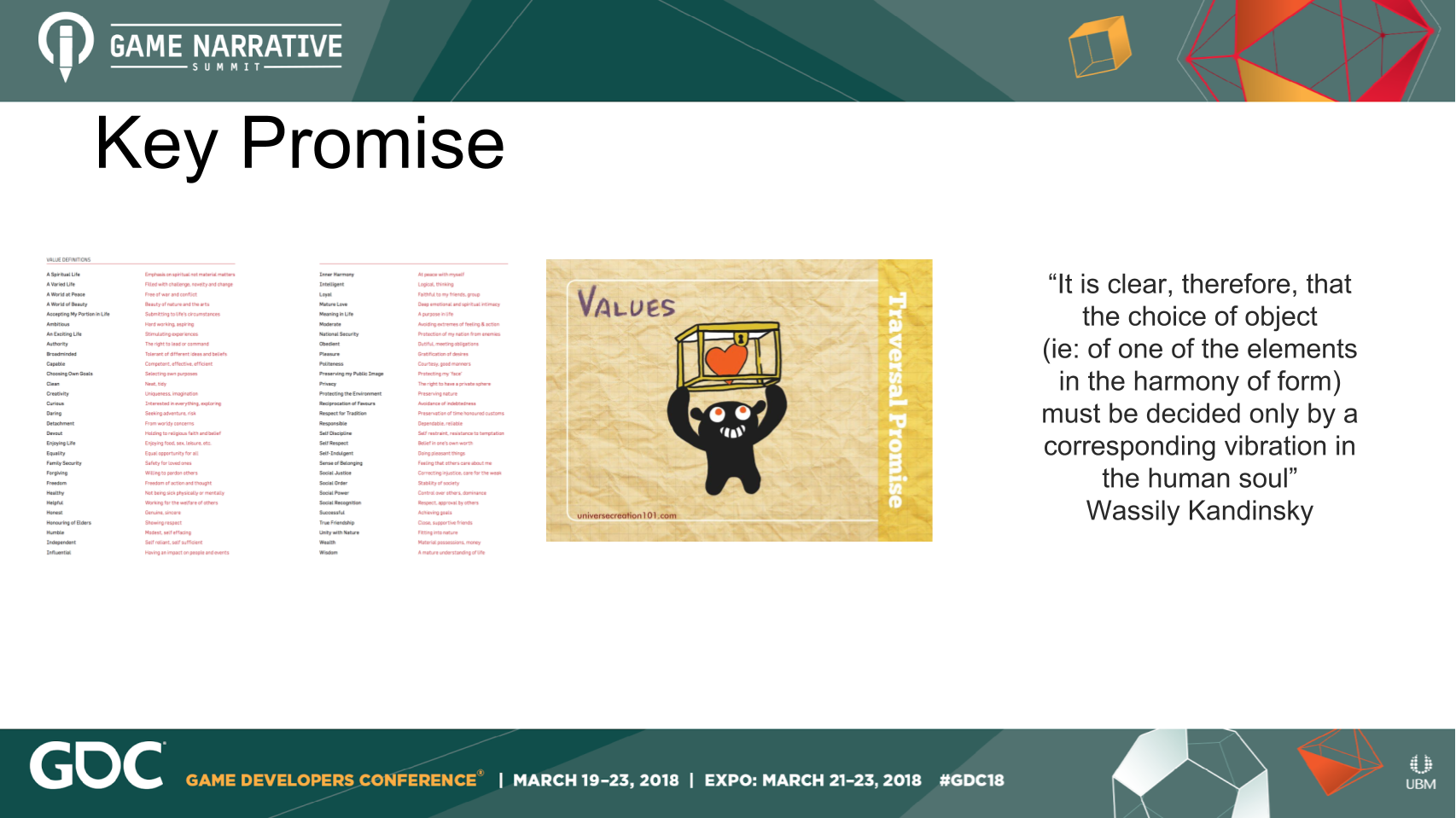

But, lastly, there is something even more powerful than all of these. It is the ultimate multiplier. It is something that once again operates in all artforms, because it operates in all people.

It is the Values Promise. The promise of giving the player something they believe in being.

Shalom Schwartz, in the Journal of Cross-Cultural Marketing, explains how our values have been shown to influence our career choices, our political persuasions, our feelings of wellbeing, and for us now, what entertainment we choose to engage with. He researched the recurring values happening across 20 countries and has published the results, which I use in my design.

Indeed, Nina Simon, the Executive Director of the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History, talks about the importance of “relevance” in drawing visitors in to museums. Nina warns that “It doesn’t matter how powerful the experience is inside the room (the museum) if most people […] choose not to enter.”

Nina explains that you need to think about your visitors, think about why they come to you, what value they get. “The more you start to matter to people, the more they will desire opportunities to go deeper […] They will come back and ask for more.”

If you don’t think about Values, they’ll still be there. They will default to the values of the status quo. But if you consciously think about them, they may be different and will resonate with players.

Take David Reilly’s Everything. You have the game, the 10 minute gameplay film the soundtrack, and the Alan Watts recordings made for the game.

Throughout all of them are the values of “Self-Direction: Independent thought and action—choosing, creating, exploring” and “Universalism: Understanding, appreciation of all people and for nature” for example.

You can be introduced to the values of the game through the film, you can purchase the soundtrack to the game to relive the game. And you can also purchase the recordings to take those words and listen to let them change you.

Creating your own indie franchise is possible. You experience lots of artforms everyday as players, it is time to practice it as designers.

Resist all the forces holding you back.

The secrets have been right in front of us.

Indeed, if we look even further back at the history of the term franchise, beyond commercialisation rights, we find that it derives from the French verb franchir, which means to ‘go beyond the limits’ of something, ‘to jump over’, ‘to cross a threshold’, to ‘give liberty to’, to ‘make free’.

So go forth and free the artforms you have inside you and make that indie franchise.

Thank you for your time.