https://soundcloud.com/christydena/i-love-playful-testing-blog-post-audio-narration

Many of you will be familiar with playtesting, or at least testing.

You sit there with a notepad and pen, watching players play your game. You write observations, you may get the players to “think-aloud,” and then afterwards you interview them, and then debrief with your team.

Tracey Fullerton describes playtesting as “something that the designer performs throughout the entire design process to gain an insight into whether or not the game is achieving your player experience goals.”¹

I understand the importance of having player experience goals, and testing to see if they are being reached. It is a key aspect of great design: to know where you want your players or your audience to end up, then retroactively design towards that; and test whether it is happening; and tweak until it is reached. Of course, the nature of the project changes in this process too.

But what if the testing was less about how our design is working, and more about how anyone’s designs are working?

I’m talking here about facilitating a playful mindset in our testers, so they shape the game in a way that brings them more joy and satisfaction.

My thinking is heavily influenced by at least two things: the monthly Remote Play sessions I’ve been running, and (the recently departed) Bernie DeKoven.

Remote Play Sessions

I run two online studios for a Masters program, and another to train studio faculty. And for the past 10 years, all my projects have been collaborations with interstate and international colleagues and clients. I can count on my hand the amount of times I’ve done co-located projects. It is normal for me to do remote work, and for many indies and studios alike.

One thing that is critical (and almost completely ignored) is the importance of team bonding and trust in the online environment. A big part of facilitating that is playing together.

But not many online games translate well for this, as they’re often competitive and anti-trust, or with high levels of skill as a barrier to entry.

So for the past few months I’ve been running an online remote play design group, where we come up and test games teams can play with each other online (via Zoom or Skype). The group began with colleagues from a lab and community I co-ran called Forward Slash Story.

Most of them in this group aren’t professional game designers, and so I needed a way to guide their design while at the same time ensuring we were enjoying the process. We also don’t have much time, and so the iteration and feedback cycle needs to be pretty short.

So what I facilitated were Designing-Testing sessions. We’re designing the game while we’re testing it.

This is actually a bit common with tabletop game testing. It is so easy to make a quick change, and if something is broken you can quickly tweak to keep the play happening.

But thinking back, I was first introduced to this design-during-play approach by Tassos Stevens in 2011. He took us through playing games and changing them as we go, as a way to learn design. (I recently wrote a play review of Bernie & Tassos’ A Game Legacy.)

And this is just what a playful mindset is.

Bernie DeKoven’s “Well-Played Game”

Indeed, this is what life-long play-advocate Bernie DeKoven explained in one of my favourite gameplay books ever: The Well-Played Game.

For Bernie, “playing well” means this: “When we are playing well,” he explains, “we are at our best. We are fully engaged, totally present, and yet, at the same time, we are only playing.”

Indeed, “the well-played game,” he continues, “is a game that becomes excellent because of the way it’s being played.”²

The key is, players are enjoying the experience so much they’ll do anything to keep playing together. Like a game of ball-in-the-air, we end up taking big leaps and give each other easy lobs to collectively keep the ball in the air.

Remember back to a time when you’re really enjoying a game with others; and they just missed putting their piece down on the board by a split-second, or their foot missed the mark by a touch, and you all decided to let it happen? That is when you’re more interested in playing well than winning.

Bernie explains the various ways we do this: the times we give hints to help our fellow players, have fair-play rules, allow small cheating, boundaries, bases and safe zones, time out, interference, and so on. These are the ways we can try and keep the game going.

Then we can also decide to adhere to the rules, but change what those rules are. As Bernie says, “it’s easier to change the game than to change the players”³

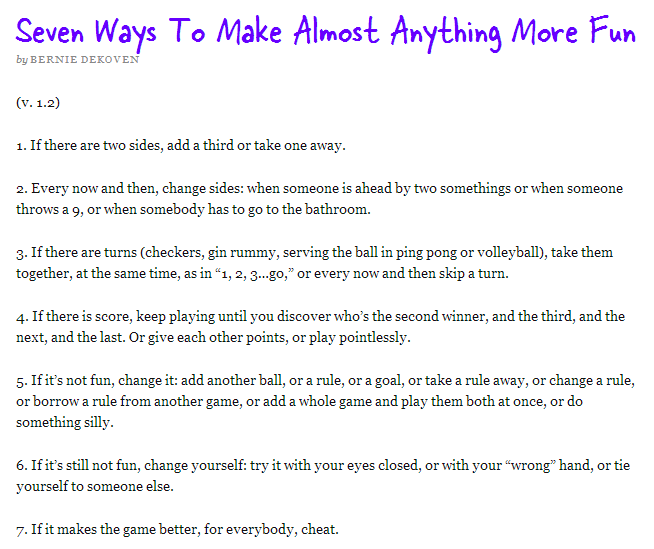

We change the rules by bending them, borrowing them, handicaps, and scoring. A post by Bernie a few years ago lists seven ways to change a game too:

But during these playful testing sessions, we’re not thinking about rule changes. We’re just thinking about whether it is allowing us to play together.

For instance, we want to do something while someone is taking their turn, so we invent a rule for what we can do during that time. Or we make it harder to draw so we come up with more awkward pictures, and so on.

I have found that it works once you set up an environment of trust, along with friendliness.

As for suggesting ideas, it isn’t just the kind of “Yes, And…” improv situation that many of you will be familiar with (where you enthusiastically go with every idea put forward). Instead, we put forward quick justifications for why we think a design tweak would be good. If people respond positively to the idea then we go for it, or if people aren’t sure then it either becomes a “let’s try it out” scenario or another idea is proposed, and so on.

What I love is:

- We’re not waiting until after the testing to hear from the players about what they think worked or didn’t, or their ideas. We’re seeing and hearing it in the moment.

- With this open design/playful design, the players are more likely to let us know what isn’t working. They’re not rationalising afterwards (though of course your interviewing and observation skills can counter this).

- I enjoy the testing more, and have my ideas pushed in interesting ways.

- It helps to pry our tight designer hands from around the project, and be open to any ideas.

- We end up having a great play experience, no matter what condition the game started in!

When To Work With This Approach?

I haven’t widely applied this approach as yet. I’m keen to though, and so my guesstimate for testing scenarios are:

- As a design-learning tool with designers and non-designers

- At the early stages of testing (first playtest etc)

- When you’ve been doing too much self-testing and confidant testing

- You need to check on your confirmation bias (we are twice as likely to see confirming information than disconfirming information, seeing our player change the game will make the latter overt)

- When you’ve hit a stalemate with your design

- To stress-test your design with unusual uses

- To inspire updates, DLCs, expansions, or new editions

Of course, this kind of testing is easier with multiplayer, live games, low-fi prototypes, and tabletop games than digital games (and especially when they’re further down the pipeline). But there may be ways around the asset manipulation issue too.

Consequences

This approach dispels the idea that the game is the end-product. That it is in a state of incompleteness–it isn’t the game–until it is finished.

What if the playtest is the experience? It certainly is for the players.

It repositions the active forces in the creation process to include all present.

It opens up ideas for your game that are outside your current idea canvas.

It facilitates a design approach that is less about producing a product, and more about the lived experience of life.

It facilitates a mindset that the world can be changed. As Bernie DeKoven said:

Learning that it is possible to change the game – that, for the sake of creating something a little more fun together, for each other – might very well turn out to be fundamental to our collective survival.³

References

- Fullerton, Tracey (2008) Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Designing Innovative Games, 2nd Edition. Burlington, MA: Elsvier, Inc, p. 248.

- DeKoven, Bernie (YEAR) The Well-Played Game. p. xxiv.

- DeKoven, Bernie (2016) It’s Easier to Change the Game than the Players, DeepFun.com

Feature photo from Scotland Now, no photographer cited.

This reminds me of me and my brothers making games when we were little.

Same! That is the way my brother and I used to make games. “And then we’ll do this, and then this will happen, and I just made up this rule…”! Super fun to do, and gives fresh insights too. 🙂

Yeah. Making changes on the fly was part of the fun.